The Indian Rivers Interlinking Project

The Indian Rivers Interlinking Project (ILR) is a large-scale, ambitious civil engineering initiative designed to manage water resources effectively across India. By linking rivers through a network of reservoirs and canals, the project aims to enhance irrigation, replenish groundwater, reduce flooding in some regions, and alleviate water shortages in others.

The idea gained momentum in 1982 with the establishment of the National Water Development Agency (NWDA) under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. In 2002, the Supreme Court directed the government to finalize a plan by 2003 and begin implementation by 2016, leading to the formation of a task force in 2003. The project gained renewed attention when, in 2014, the Ken-Betwa River Linking Project received cabinet approval. Since then, the NWDA has developed reports on 14 river links in the Himalayan region, 16 in the peninsular region, and 37 intra-state links.

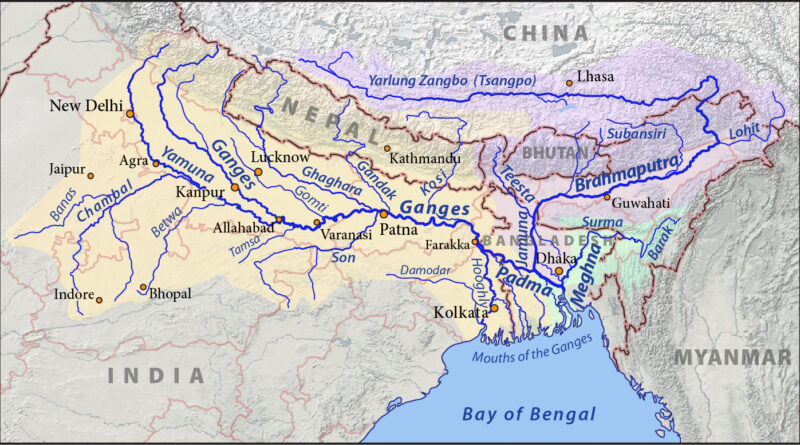

The ILR project envisions 30 river linkages, 36 dams, and 10,800 km of canals, divided into three components: Northern Himalayan River Interlinking, Southern Peninsular River Interlinking, and Intra-State River Interlinking.

Advantages of the ILR Project

The ILR project is expected to address both drought and flood challenges. For example, water-surplus regions like the Ganga and Brahmaputra basins could transfer excess water to deficit areas, reducing annual floods. Although energy-intensive, the project may decrease reliance on domestic hydropower by expanding collaboration with Bhutan for hydropower imports.

Indian agriculture depends heavily on monsoons, leaving farmers vulnerable during low-rainfall years. By improving water access through river interlinking, the ILR project could stabilize agricultural yields, reduce migration to cities, and spur rural economic growth. Additionally, the ILR project will generate significant employment during construction and maintenance, contributing to economic resilience. The Ken-Betwa, Godavari-Krishna, and Par-Tapi-Narmada link projects stand as prominent examples of interlinking ventures with promising benefits.

Advanced technologies, including Geographic Information Systems (GIS), satellite imagery, and computer modelling, are helping to map routes, calculate water flow, and assess environmental impacts, ensuring data-driven decision-making and efficient resource management.

Challenges Facing the ILR Project

India’s water security issues are complex, with over-extraction of groundwater, pollution, poor distribution systems, climate change, and water disputes threatening sustainability. River interlinking, especially for rivers crossing state boundaries, often encounters legal hurdles and political resistance. States are cautious about losing control over water resources, fearing impacts on local economies and ecosystems.

The project also faces significant engineering challenges, such as soil stability, seismic risks, and energy demands for water transfer across varying terrains. Land acquisition poses another major obstacle: large tracts of land will need to be acquired for canals, which may displace numerous communities. Ensuring adequate resettlement and compensation will be critical to avoid social disruptions.

Funding the ILR project is a daunting task, given India’s need to invest in health, education, and infrastructure. International concerns are also pertinent: neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan may experience reduced water flow if projects on rivers like the Ganges and Brahmaputra alter natural patterns. Transparent communication and cooperative agreements on water sharing will be essential for preserving regional stability.

Government Initiatives Supporting the ILR Project

The Government of India has taken several proactive steps to support the ILR project. Programs like the Namami Gange and the National Plan for Conservation of Aquatic Ecosystems (NPCA) aim to improve water quality and build water infrastructure. Sewerage infrastructure projects under the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and the Smart Cities Mission also complement ILR goals by improving water management at the urban level.

The NWDA, responsible for overseeing the ILR project, has identified 30 river interlinking projects, to be funded 60% by the Government of India and 40% by state governments. All ILR projects have been declared national projects, fostering cooperation through inter-state agreements and collaborative planning. The government is also promoting environmentally friendly engineering practices, such as constructing fish passages and reforesting canal areas, to minimize ecological impacts.

The Future of Water Security in India

India’s river-linking projects are set to transform water security by transferring surplus water from flood-prone areas to drought-affected regions. With projected business opportunities worth ₹2 lakh crore for engineering, procurement, and construction over the next decade, the ILR project could also stimulate economic growth.

Advanced technologies like hydrological modelling, smart irrigation, AI-powered maintenance, and water purification are set to make the project both efficient and sustainable. Drones and satellite monitoring will enable real-time environmental assessments, while climate-resilient infrastructure will help buffer against extreme weather. Public participation platforms will foster transparency and community involvement, encouraging collaboration for sustainable water management.

Conclusion

The Interlinking of Rivers Project is a bold step toward addressing India’s water scarcity, flood management, and agricultural needs. Its implementation could drive economic growth, improve water accessibility, and strengthen disaster resilience. However, challenges remain—financial, environmental, and social. A successful ILR project will require careful planning, collaboration among states, and a commitment to ecological preservation, balancing development needs with environmental sustainability.

For more such interesting blogs, visit: https://vichaardhara.co.in/